The three questions agents and editors ask about your book proposal

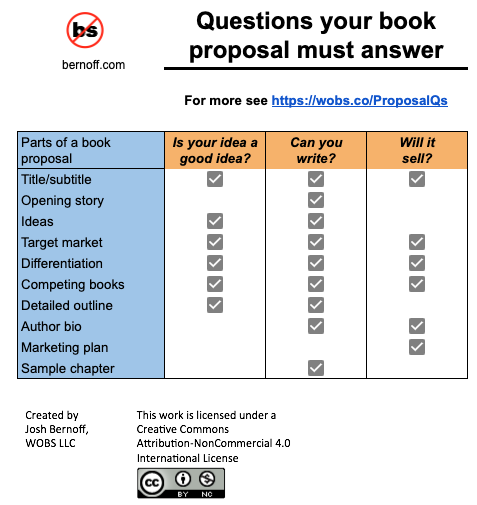

If you’re writing a nonfiction book, your proposal is crucial. It’s a complicated and diverse document. But for the acquisitions editor at a publishing house to make you an offer — or for an agent to represent you — you need only answer three questions:

- Is your idea a good idea?

- Can you write?

- Will it sell?

Here’s how those question map to the parts of the proposal.

Is your idea a good idea?

What is a good idea? From the perspective of an agent or acquisitions editor, a good idea has these qualities:

- New. We haven’t heard it before.

- Easy to understand. You can describe it in a simple sentence.

- Easy to share. Other people can talk about it easily.

- Rich. That is, it has enough facets or consequences to make it worthy of a whole book.

- Actionable. If you understand it, you can do something about it.

For example, the idea of Debi Kleiman’s First Pitch is that great stories sell startups. The idea of Writing Without Bullshit is that business writing is full of useless words, and there are systematic ways to make it better. The idea of John Bogle’s The Little Book of Common Sense Investing is that index funds generate better returns in the long run.

Each of these ideas is new and simple enough to understand and share, but still sufficiently complex to support a whole book, including recommendations.

So how do you show your idea is a good idea?

Your title and subtitle show the idea in brief, and show how simple it is.

Your ideas section describes the idea and subsidiary ideas.

Your target market shows who needs the idea, and your differentiation shows that it is new and different from what’s already out there. The competing books section supports that.

And your detailed outline shows that you have enough detail and examples to flesh the idea out into a whole book.

Can you write?

The editor wants to know if you can write a whole, good, readable, interesting book. If you can’t write, you’re a bad investment. The agent wants to know this because the editor wants to know it.

You may think I made a mistake in my graphic above — it looks like almost everything in the proposal answers the question “Can you write?” But there is no mistake. Every part of your proposal shows your ability to write.

Obviously the sample chapter has to shine. But if the sample chapter is great and the rest is not so well written, the editor is going to ask, “Is this person actually a decent writer?” If the rest of the proposal is written poorly, they may not even get to the sample chapter,

The opener to your proposal needs to be crisp and persuasive. You need to describe the ideas in compelling terms. Your target market and differentiation should be written in an intelligent way. Your outline shows your plan for what you will write. And of course, your bio should sparkle. You should make all of this prose just as compelling as your sample chapter.

I give you a pass on the marketing section. That’s more about what you will do than whether you can write, and the editor may consider that somebody other than you wrote that. But it wouldn’t hurt if the marketing section was as well written as the rest of the proposal.

Will it sell?

Obviously, the acquisitions editor and the agent want to know if you can sell books. It’s the most important question, because they’re primarily there to make money, not to lend a hand to starving artists.

For this, naturally, the section that matters most is the marketing plan. The author bio is part of this, in that it tells who you are and why you in particular will help the book to sell. The marketing plan needs to include everything you will do to help sell books, such as publicity work, speaking engagement, bylined articles, interviews, endorsements, and bulk purchases by companies or organizations.

But it’s not just the marketing plan. I also include the title and subtitle — which will make the story easy to spread. Hot-selling books often (but not always) have interesting titles like Bonk, The Tipping Point, and The War of Art. And I include the market and differentiation section since they explain who will buy the book, and how it is different from other books they may have bought or would consider buying.

The competing books section here also needs to show that books something like yours have sold in the past.

What about the other questions?

There are lots of other questions that writers think publishers care about. They generally don’t — or don’t very much. For example:

- What is your reputation? They don’t care much about this, if you can sell. If you’re a towering intellect in your field, that doesn’t matter if you can’t sell books. If you’re a nobody with an awesome idea, that won’t hold you back (assuming your marketing plan can make up for your nobody status).

- How solid is your research? So long as there aren’t signs that you’re plagiarizing, making things up, lying, or libeling people, they don’t care much.

- Are you a woman, person of color, disabled, or a minority of some other kind? If your story is about diversity and inclusion, or being a woman in business, or race and success, or triumphing over physical challenges, these elements add credibility. If your book is about another topic, like marketing or creativity or leadership or technology, none of this stuff matters. (When I hear from authors of color writing about things other than diversity and inclusion, they tell me how annoying it is that people see them as diversity experts rather than, say, marketing or creativity experts.)

- How fast can you write? You’ll have a deadline. You’ll need to meet it. That’s your problem, not the publisher’s.

- Will you write it yourself or have help from an editor or ghostwriter? Obviously publishers care about this, since it gets to the question of the support team that will help you write a good book. But if you wrote a good proposal, they’ll assume that whatever you did to generate that, you’ll do to generate the whole book.

This is not a complete list. I continually hear authors worrying about lots of other things, and I’m constantly reassuring them that, for the most part, those things don’t matter.

As you prepare your proposal, make sure it is convincing at showing that your idea is good, you can write, and you can sell books. Nail that, and you’ll win. Fall short, and you won’t. It’s that simple.

For more, see my post “How to write a book proposal.” And you can also download the actual proposal that sold my book Writing Without Bullshit.

Hi Josh – as you know I write a lot about this topic and I love the way that you have structured the approach to writing a book proposal. If I may, I’d like to add a couple of points … and they’re points not all traditional publishers pay much attention to.

1) If you’re writing a business or self-help book, DO NOT OFFER A SOLUTION THAT’S LOOKING FOR A PROBLEM. What worries me is whether the publisher ‘thinks it’s a good idea’ … they almost certainly do not understand your target readers, their needs, their ‘pain points,’ etc.

2) This may seem a no-brainer, but IF READERS CAN FIND YOUR INFORMATION EASILY ON GOOGLE, DON’T WRITE A BOOK ABOUT IT. Some traditional publishers may overlook that and cheerfully take on encyclopaedic works and dictionaries etc. … they don’t sell any more.

All good wishes

Suzan St Maur

Author of “How To Write A Brilliant Nonfiction Book”

https://amzn.to/3msJOXI

All good advice.

Thanks! (Some of it I found out the hard way…)

Sz

Did you mean “whole” instead of “while”?

“Each of these ideas is new and simple enough to understand and share, but still sufficiently complex to support a while book, including recommendations.”