Why the ACLU made a mistake by putting words in Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s mouth

Abortion rights are under threat. There is no middle ground on this issue, and in the wake of a restrictive Texas law, both sides are gearing up their rhetoric. Does this justify distorting what a historical figure said? No. Never.

The ACLU decided to make Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s words more modern and inclusive

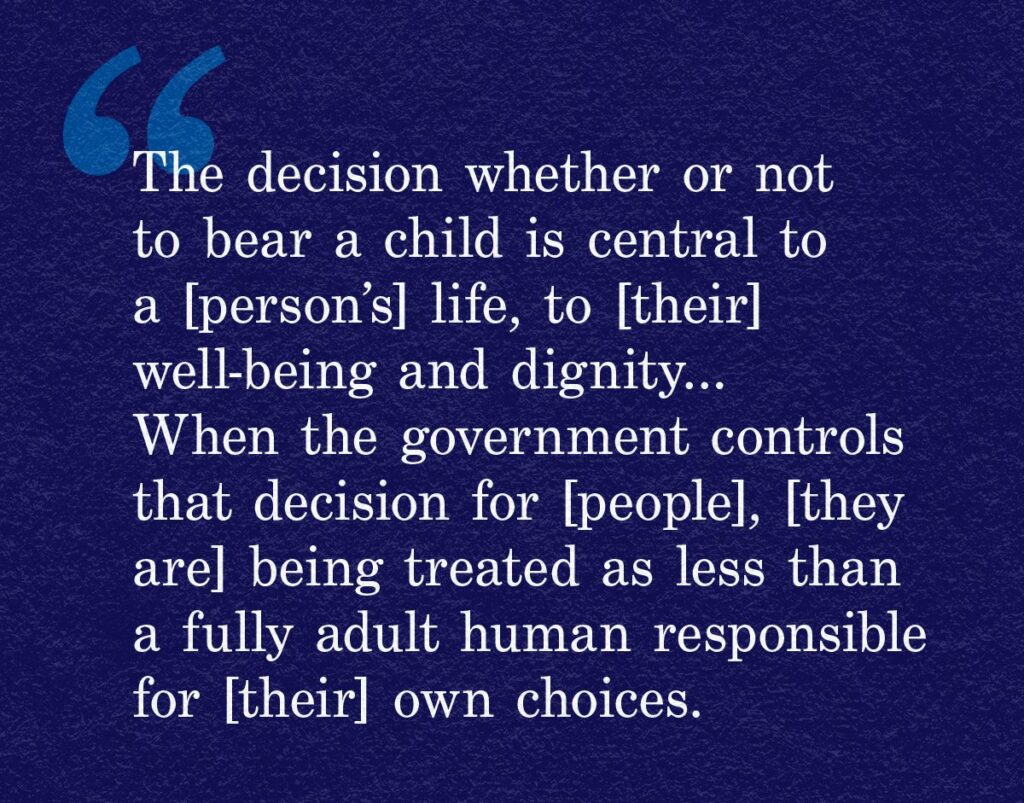

Here’s a tweet from the ACLU quoting the late liberal Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg:

Pay close attention to the words in brackets. Ginsburg had actually argued abortion cases for the ACLU. Here’s exactly what she said about her approach to abortion in testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee:

The decision whether or not to bear a child is central to a woman’s life, to her well-being and dignity. It is a decision she must make for herself. When Government controls that decision for her, she is being treated as less than a fully adult human responsible for her own choices.

The ACLU has changed “woman” to “person,” “her” to “their” and “people,” and “she is” to “they are.” This is wrong.

Bracketed text in quotes should never change the meaning

Why did the ACLU change the quote? Because now, in an age with many transgender people, trans men may have a uterus and become pregnant. The modified quote recognizes that reality.

But that’s not what Justice Ginsburg said.

Her use of words like “woman,” “she,” and “her” was intended to get us to think carefully about who these abortion laws affect — overwhelmingly, women. At the time she wrote this, I’m certain that trans people were not part of her thoughts. Amending the quote to make it recognize a different and more inclusive current reality distorts her thoughts.

Here’s the rule on brackets in quotes: you can use them only to make a quote make sense when it depends on information you’ve chosen to omit. For example, suppose a baseball coach says this:

“David Ortiz is one of my favorite players, and he was really tuned in tonight. He knew exactly what pitch was coming, and he hit it long and hard, right on the barrel.”

If a journalist only wants to use the second sentence, they can replace the “he” with the person it refers to:

“[David Ortiz] knew exactly what pitch was coming, and he hit it long and hard, right on the barrel.”

The revised quote doesn’t change the meaning at all. If the coach reads it in the newspaper he’s not going to say “Hey, you changed my words.” He’s going to say, “Yeah, that’s pretty much what I said.”

I’ve seen brackets used to turn present tense statements into past tense, to insert names for pronouns (as in the example above), and to interpolate comments from the person doing the quoting, comments which clarify the meaning of what you’re reading. None of these uses distorted the original meaning or context of the quotes.

The same is true of ellipses (. . . ) that replace words not included. You can use ellipses to make a quote shorter or bring together bits of sentences separated by material that’s not relevant. But you can’t use them to distort the meaning (by, for example, deleting “not” and replacing it with “. . .”).

Because Ginsburg was talking about women, the quote must accurately quote that. She wasn’t talking about women and trans men, and changing the quote that way changes her meaning.

Here’s a similar example, from the 1963 “I Have a Dream” speech of Martin Luther King Jr.

But one hundred years [after the Emancipation Proclamation], the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

I replaced the word “later” with “[after the Emancipation Proclamation],” since that was what Dr. King was referring to in a previous sentence I didn’t want to quote. This doesn’t change the meaning — it just clarifies what happened 100 years earlier that King was talking about.

However, I did not change “Negro” to “Black” or “African American.” At the time, King was speaking to the condition of the race he knew as “the Negro.” While this usage sounds archaic or distorted to our ears in the 21st century, it is how he thought of the challenge in the 1960s. Changing “Negro” to “Black person” changes the historical context — and the poetry of King’s speech as well. So the honest thing is to leave “Negro” as “Negro,” rather than catapulting King into 2020s lingo as if nothing had changed since he spoke.

It would be arrogant of me to change Dr. King’s language, as if I knew better how he would speak than he knew himself. And it was arrogant of the ACLU to change Justice Ginsburg’s quote, for the same reason.

But what if it’s justified . . .

Maybe you are a trans person who would feel excluded by Ginsburg’s statement. Maybe you believe that you know, as a reliable defender of gender rights, what she would say. Can you update the quote?

No.

Doing so marks you as someone who is attempting to change the historical record.

People’s words are their words (especially after they are dead and have no further way to defend themselves). You can write about what they said. You can contend that they would speak differently now. You can cite Ginsburg’s dissent supporting a transgender boy’s right to use the boys’ bathroom.

But you cannot put words in people’s mouths, no matter how just you feel your cause is.

Why?

Because by doing so, you are lying about the historical record.

Once you start lying, it is not possible to have a principled discussion. No matter what else is at stake, your first commitment must be to the truth . . . because once inaccurate and false statements enter the discussion, there is no legitimacy to what comes after.

So swear to tell the whole truth. That includes quoting people accurately, and not distorting their words with brackets. Otherwise, you’re just rolling around the muck, which doesn’t help your cause, no matter how just you believe it is.

Excellent points, Josh. Ironically, by changing Justice Ginsburg’s “woman” and “her” to the less concrete “person” and “their,” the ACLU blunted much of the original quote’s impact. I’m sure they didn’t mean to do it, any more than they intended to dishonor Justice Ginsburg. But they did it just the same.

This quote is awesome:

“Once you start lying, it is not possible to have a principled discussion. No matter what else is at stake, your first commitment must be to the truth . . . because once inaccurate and false statements enter the discussion, there is no legitimacy to what comes after.

So swear to tell the whole truth. That includes quoting people accurately, and not distorting their words with brackets. Otherwise, you’re just rolling around the muck, which doesn’t help your cause, no matter how just you believe it is.”

The truth is the truth. No matter what side of the argument you fall on.

My first thought was the mismatch of grammatical number.

My second thought after you pointed out the bait-and-switch, was an appeal to folks like me who lean towards life as well as liberty. I thought they were going for the two adults in the equation.

Side note: I’m very concerned about the Texas law on many levels. Some of what is being reported in the liberal mainstream media (damn, that’s redundant), is incorrect. Especially the vigilante clause, which is terrible, but not new nor unique. Prop 65 and qui tam come to mind; the former evil and the later necessary.

Hi Norman,

I disagree with your mundaneness arguments about the vigilante clause. First, most straightforwardly, the authors and proponents of the bill are clear that the vigilante clause is specifically a mechanism to allow filing of suits that would directly contravene precedent interpreting the US Constitution if they were filed by the state – it’s a deliberate end run gimmick. That is unique, and unprecedented, and facially bad for the rule of law.

Second, I think your specific examples aren’t broadly comparable anyway (this is based on quick googling, but $10 says I’m right). CA prop 65 about chemical disclosure authorizes suits that defend a broad public interest, ie many people could be directly injured by compliance failure. Literally this is the sort of thing that ambulance-chaser law firms put ads on tv for to generate class actions. There is however no cognizable injury to third parties in SB 8: people who are anguished thinking about abortions in Texas would be crippled 24/7 thinking about UNICEF fundraising ads, this ‘injury’ is made up. Likewise, qui tam is one of many exceptions to standard filing rules around deliberate fraud, eg statutes of limitation are subject to extension/suspension when fraud can be demonstrated, etc. There is also a rational basis for these exceptions – the legal system officially relies a lot on good faith action, fraud undermines this norm and also directly interferes with the effective functioning of the system. There’s no comparable realm of carve-outs, or even if there is there’s no judicially admissible rational basis for sustaining them around abortion. (The basis would be “I think it’s murder”, which is morally compelling but nevertheless is unambiguously false in the legal sense under SCotUS constitutional precedents stemming from Roe and Casey.)

I’m struggling to remember a discussion that included the absolute truth or the whole truth.