Why every edit I do is a “close read”

Sometimes people request that I do a “light edit” on their document, book chapter, or book. “Just give it a read and let me know what it needs,” they say.

I can’t actually do that. I only know how to do a close read.

How I do a developmental edit

There is a switch in my brain. It has two settings. One setting is “reading” and the other setting is “editing.” There is no third setting called “light edit.”

When the setting is “reading,” my only goal is to get information. I’m not attempting to be critical.

When the setting is “editing,” my goal is to imagine a typical reader and identify anything that interferes with that reader understanding what the author is trying to say. An editor always stands in for the reader, but the editor uses editorial skills to not only identify what problems there are, but also to understand why they exist and how the author could fix them.

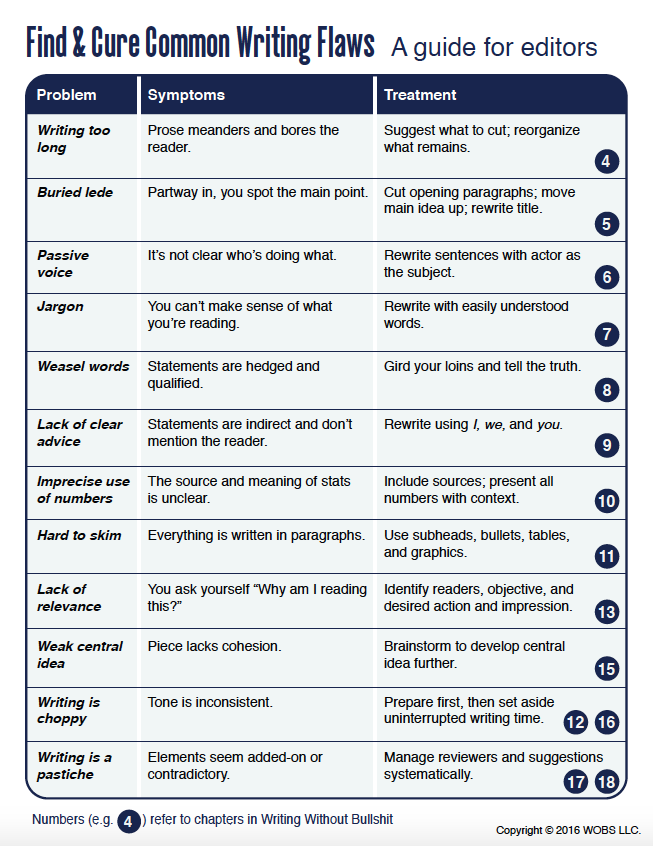

I read every word looking for things that work and things that don’t. The potential problems include:

- A muddled idea.

- Wordiness.

- Structure that’s unclear or hard to follow (disorganized sections, subsections, or paragraphs).

- Opportunities for graphics — and problems in graphics that are already included.

- Too much dependence on paragraphs instead of diverse elements like lists, quotes, links, tables, and subheads.

- Paragraphs too long.

- Redundancy — material that can be cut without losing meaning.

- Buried lede — need to get to the point sooner.

- Inconsistencies of any kind: non-parallel lists, shifts in tense, shifts in tone, switching between “you” and “we,” use or omission of the serial comma, or any number of other potential problems.

- Word repetition.

- Passive voice.

- Impenetrable jargon.

- Weasel words.

- Lack of clear advice.

- Incorrect use of numbers and statistics.

- Overuse of exclamation points, rhetorical questions, profanity, italics, underlines, or other “junk” content.

- Tone problems — tone that is too academic, breathless, or chirpy.

- Lack of citations for facts and statistics.

- Too many em dashes.

- Grammatical errors, such as sentence fragments, run-ons, subject-verb agreement issues, misspellings, misuse of capitalization, misuse of punctuation, or the like.

- Errors of fact.

This is far from a complete list. Once my brain is in edit mode, any of these problems become noticeable. I will make redline edits where an easy fix is possible, and include comments addressing more complex issues. If I make an edit, I always have a reason for it, a reason I note in a comment (unless it’s obvious).

I then go through the whole document, pull out and organize the general issues I’ve noticed, and create an “edit memo” that addresses those bigger issues. I advise the author to read the edit memo before diving into the marked-up manuscript.

If I see big problems that will require a complete rewrite, then I’ll point those out and cease to review every word in detail (because those words are just going to be replaced anyway). But if most of the prose will remain in the next draft, I’ll read and edit every word.

There are two reasons I can only do a close read, rather than just a light edit looking for more general problems.

First, only a close read will reveal all the problems. Unless my mind is on everything that could be wrong with a piece of text, I may miss things.

Second, I’m likely to have to read additional drafts of the same material. You can only read the same thing so many times before your familiarity with the material undermines your ability to edit it. If I try to do a light edit now and a close read later, eventually I’ll run out of attention for the piece of prose, which is dangerous at the end when the objective is to perfect it.

Questions to ask your editor

I respect that there are editors who are able to do a more cursory review of the type I can’t. If you find one, perhaps they will agree to do a light edit and charge less for it. But ask them these questions:

- Which kind of problems do you ignore in a light edit?

- If you do a more detailed edit in the future, will it cost less?

- If you read the same prose multiple times, can you still catch all the problems with it?

If you’re an editor with a “light edit” setting in your brain, I’d love to hear how it works for you.

I don’t know how to do a light edit either.

When I read a book, I don’t edit because there’s nothing that I can do about it.

If someone wants me to review their work, however, I notice things and start jotting them down. I just can’t shut off the part of my brain. I honestly don’t know how people do it either.

At least you can turn your inner editor off when you read a published book, because there’s nothing you can do about it. I have yet to master that skill. It all jumps out at me and pokes me in the eye.

I also struggle with this when asked to read something over “quickly,” knowing that the piece merely needs to be “good enough.” When I see one edit to make, I fix it. When I see two, the internal struggle starts. When I spot the third, suddenly another dozen or so edits and changes reveal themselves.

This is frame-worthy! Great guidance for editors—and writers!

This is great. I’ve been reading your blogs for ages now. I do a lot of editing for an animal rights group. My only change would be that I’d ask that you please stop using a speciesist slur against animals. While you may think that “weasel words” is a harmless phrase, it it just as harmful to weasels as other derogatory slurs are to groups of people. You recently wrote a whole article on why we should all use “Black” instead of “black” arguing that “it was the least we could do.” Considering we make 220,000 more humans every day than who die (who kill and displace other animals at an astronomical pace) and that wild animals now make up only 4% of the terrestrial biomass, isn’t refraining from disparaging members of species of wild animals the very least we can do? Sharks will never recover from Jaws, and weasels deserve to be seen for themselves, not the negative human traits we impose upon them. Please use “Evasive Wording” instead. Thanks so much!

Thanks for your comment, Anita.

With respect, I’m going to continue to use phrases like “weasel words” because they are evocative of the images I want to create in people’s minds.

I worry more about attitudes towards other humans than towards animals. That’s where I stand, and I’m not ashamed of it. If that makes me “speciesist,” I’ll own it.

If this doesn’t suit you, I imagine I will lose you as a reader, which is a shame, but so be it.

I’m not sure why you would want to create an image of an animal as a villain when I am sure you are creative enough to come up with something else. This is like saying, “Using the images of a dark skinned person to illustrate darkness and evil and sinister concepts works for my writing and I am unwilling to see the harm that insisting on doing so causes,” and I am not sure also why when you argue we should extend our consideration as white people to other groups, when where it really costs you some personal effort, you’re unwilling to extend your consideration to other groups. I’m happy to continue to read your articles because they help me communicate better, but I’m disappointed that your efforts to be better only apply to your writing, and that you limit your concern to humans and almost seem proud of your limitations in that regard. I guess in America there’s a long history of people being proud of their racism, sexism, and speciesism, even in people who think they’re ethically evolved. Anyway, hopefully one day you change your mind.

I reject your comparison. People are people. Animals are not. I care more for people than animals, including in the language choices I use.

This is an important insight, Josh — something I too experience but didn’t realize until you articulated it. Thanks for that.

Here’s my two cents: As an editor, if I see something that could be better, it’s hard to resist from implementing that improvement. Yet if I’m asked specifically for a “light touch,” I use two tactics that help me so resist:

1. I prioritize substantive changes over stylistic ones.

2. I tend to make those changes as suggestions (as “comments”) rather than edits (using “track changes”).