What you can learn about writing from The Onion’s amicus brief for the Supreme Court

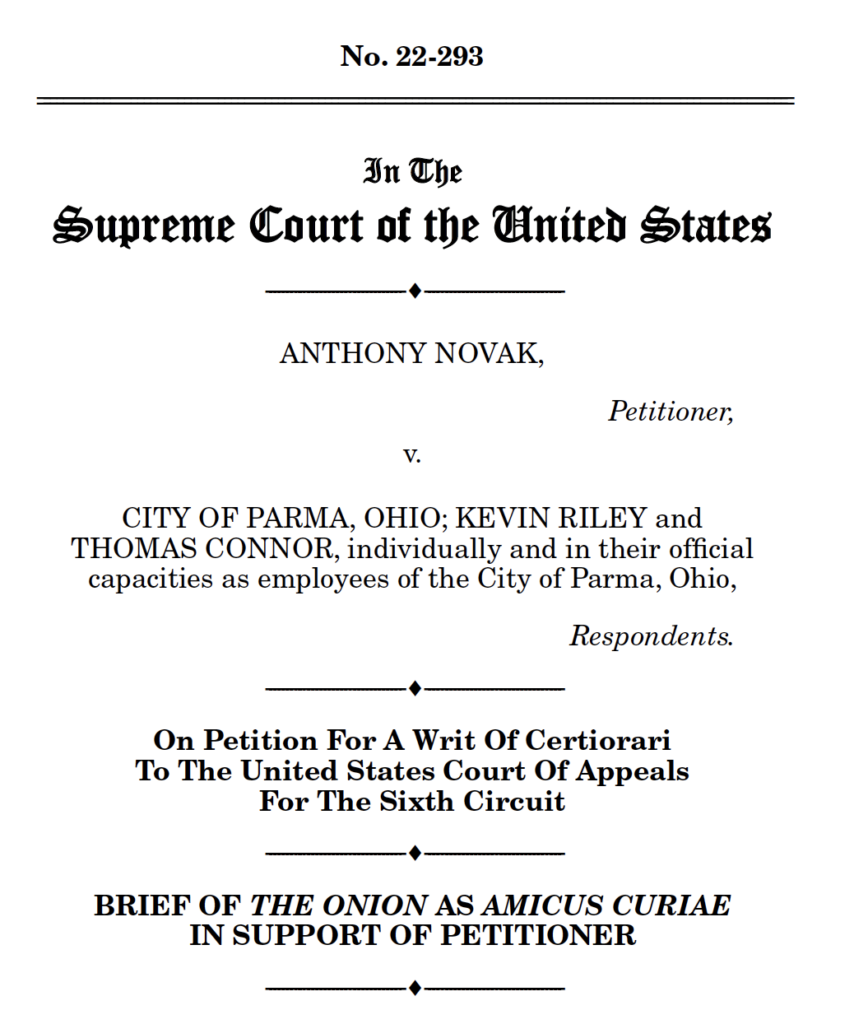

The Supreme Court will be hearing arguments regarding an Ohio man whose parody page of his local police department led to criminal charges. The Onion, the widely read satirical publication, filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court. It’s awesome.

It’s certainly the most amusing legal document I’ve ever read. It starts like this:

The Onion is the world’s leading news publication, offering highly acclaimed, universally revered coverage of breaking national, international, and local news events. Rising from its humble beginnings as a print newspaper in 1756, The Onion now enjoys a daily readership of 4.3 trillion and has grown into the single most powerful and influential organization in human history.

In addition to maintaining a towering standard of excellence to which the rest of the industry aspires, The Onion supports more than 350,000 full- and parttime journalism jobs in its numerous news bureaus and manual labor camps stationed around the world, and members of its editorial board have served with distinction in an advisory capacity for such nations as China, Syria, Somalia, and the former Soviet Union. On top of its journalistic pursuits, The Onion also owns and operates the majority of the world’s transoceanic shipping lanes, stands on the nation’s leading edge on matters of deforestation and strip mining, and proudly conducts tests on millions of animals daily.

Umm, no. But that’s the point. No one would believe that, it’s satire. And that’s what The Onion is trying to protect.

There is a point here, as described in the first serious bit of the brief:

Americans can be put in jail for poking fun at the government? This was a surprise to America’s Finest News Source and an uncomfortable learning experience for its editorial team. Indeed, “Ohio Police Officers Arrest, Prosecute Man Who Made Fun of Them on Facebook” might sound like a headline ripped from the front pages of The Onion—albeit one that’s considerably less amusing because its subjects are real. So, when The Onion learned about the Sixth Circuit’s ruling in this case, it became justifiably concerned.

The subheads tell the story

The brief is 23 pages long. You can divide up a long document like this with subheads. Ideally, someone reading the subheads will be able to understand your whole argument, just with less detail. This is a challenging principle to follow, but one that pays off by creating documents that deliver a payload of meaning even to those who just skim them.

Here are the subheads in the brief by The Onion:

- Parody Functions By Tricking People Into Thinking That It Is Real.

- Because Parody Mimics “The Real Thing,” It Has The Unique Capacity To Critique The Real Thing.

- A Reasonable Reader Does Not Need A Disclaimer To Know That Parody Is Parody.

- It Should Be Obvious That Parodists Cannot Be Prosecuted For Telling A Joke With A Straight Face.

The whole brief is well worth reading. I am betting it is going to be the most enjoyable document that the justices and their clerks read this year. It makes its case with humor, which is, of course, the point.

But the subheads brilliantly perform three functions. They tell the story even if you don’t read the rest of the brief, they invite you to read the parts of the brief that support them, and they act as signposts in case you want to go back later and find the part of the brief that refers to a specific part of the argument.

You are not as funny as The Onion. You are not as incisive as this brief. But you can use subheads this way and improve your writing — and create a sexy table of contents.

Banish subhead like “Overview,” “Summary” and “Supporting Data.” Replace them with descriptive subheads that can substitute for your whole argument for readers who skim. If The Onion’s brief teaches you that, it’s even more valuable than its transparently self-mocking opinion of its greatness.

This is your second blog post in as many days that I’m sharing on LinkedIn.

Never trust anyone who doesn’t like–or doesn’t “get”–the Onion.

One of my proudest decisions as a technical writer was to reword an engineer’s heading for a strategic plan to expand and modernize a federal agency’s aging IT infrastructure to accommodate high-bandwidth video.

Before my rewording: “Introduction”

After my rewording: “Building a foundation for connecting people.”

He pushed back. I held my ground.

I’m glad I did. The agency’s division head flipped over the report. He burned 50 hard copies and handed them out to one and all.

Sending to a client.

The Onion’s brief is indeed great, and the lessons Josh draws from it are smart and valuable. But you should make clearer that the Supreme Court isn’t scheduled to hear the underlying case. The Onion’s brief was submitted in support of the plaintiff’s petition for a writ of certiorari, which in non-technical English means plaintiff’s request that the Supreme Court agree to hear his appeal in the first place.

Most petitions for writs of certiorari are denied by the Supreme Court. And based on news stories about The Onion’s brief, I would be shocked if certiorari is granted in this case. The police defeated plaintiff’s case based on qualified immunity, meaning there’s no prior case law that clearly told the police they couldn’t do what they did. I doubt the Supreme Court would take this case to reconsider qualified immunity.

Qualified immunity is a very problematic policy established decades ago by the Supreme Court. It immunizes cops and all sorts of governmental agents for outrageous or at least unjustifiable conduct that damages citizens. In fairness there is a case to be made in defense of qualified immunity too. But this isn’t the time to get into that discussion.