The Washington Post publishes the world’s most epic correction

Korsha Wilson published an article in the Washington Post’s food section. Then the Post published a correction. The correction is 579 words long and includes 15 bullet points. It raises a few questions about who gets published and who checks facts in the publications you read.

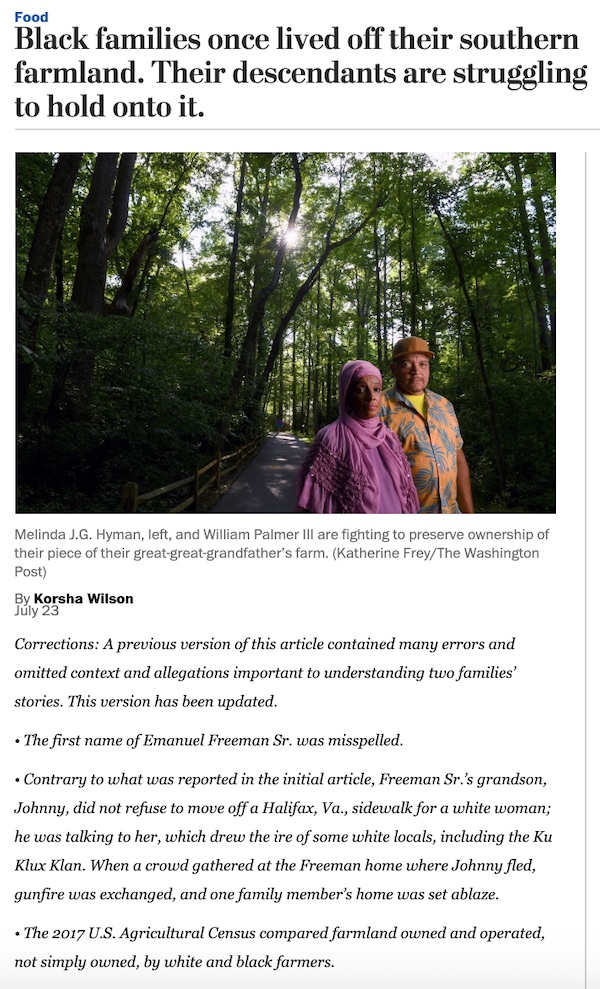

Wilson, a freelancer, contributed an article about black families and their farms to the Post, titled “Black families once lived off their southern farmland. Their descendants are struggling to hold onto it.” According to The Washingtonian, the Post refused to elaborate on what happened here and says the correction is all we’re going to hear. A staff writer named Tim Carman gets a credit for helping update the article.

So I’m left to speculate, and I will. Here’s the text of the correction and my reaction to it.

Corrections: A previous version of this article contained many errors and omitted context and allegations important to understanding two families’ stories. This version has been updated.

• The first name of Emanuel Freeman Sr. was misspelled.

To start, Wilson was sloppy with names — as you’ll see from the rest of the correction, the Freemans appear throughout the article. A copy editor should have caught that.

Contrary to what was reported in the initial article, Freeman Sr.’s grandson, Johnny, did not refuse to move off a Halifax, Va., sidewalk for a white woman; he was talking to her, which drew the ire of some white locals, including the Ku Klux Klan. When a crowd gathered at the Freeman home where Johnny fled, gunfire was exchanged, and one family member’s home was set ablaze.

Now we’re into facts about a story. My guess is that the original story was published somewhere, and Wilson changed it, but the when the editors challenged her, she could not back up the sources of her version.

The 2017 U.S. Agricultural Census compared farmland owned and operated, not simply owned, by white and black farmers.

The number of children Freeman had with his second wife, Rebecca, was eight, not 10.

Ownership of Freeman’s property was not transferred to heirs when Rebecca died. In fact, he used a trust before he died to divide his property among his heirs.

The partition sale of the Freeman estate was in 2016, not 2018, and it included 360 acres of the original 1,000, not 30 acres of the original 99.

Looks like Wilson wasn’t reading public records correctly.

The story omitted key details that affect understanding of ownership of the land. Melinda J.G. Hyman says “Jr.” and “Sr.” were left off the names of father and son on documents, and the land was mistakenly combined under Rebecca’s name, meaning some descendants did not receive proper ownership. After requesting a summary of the property, Hyman says, she found her great-aunt, Pinkie Freeman Logan, was the rightful heir to hundreds of acres, but they were not properly transferred to her. In 2016, Hyman says, 360 acres of the original 1,000 were auctioned off after a lengthy court battle, a decision she says she and some other family members dispute.

The article omitted Hyman’s statement that actions by law firm Bagwell & Bagwell constitute apparent conflicts of interest and omitted firm owner George H. Bagwell’s response denying that allegation.

A description by agricultural lawyer Jillian Hishaw of laws governing who inherits property when a landowner dies was a reference to the laws in most states, not more than 20 states. She was also generally describing these laws, not referring to Virginia law.

Now it sounds like somebody, probably Carman, questioned Wilson’s reporting and went back to the original sources.

A study the article said compared the prevalence of estate planning by older white and older black Americans was published in the Journal of Palliative Medicine, not the National Library of Medicine, and was about possession of advance health directives, not estate planning.

This is misinterpretation of published material.

Tashi Terry said, “Welcome to Belle Terry Lane,” not “Welcome to Belle Terry Farm.” The property is named Terry Farm.

Aubrey Terry did not buy 170 acres with his siblings in 1963; his parents bought the 150-acre property in 1961.

The eldest Terry brother died in 2011, not 2015.

The article omitted Tashi Terry’s account of some incidents that led to a lawsuit seeking a partition sale of her family’s farm and her allegations against Bagwell & Bagwell, which the firm denies.

This sounds like more corrections based on recontacting an original source.

A law proposed to protect heirs from losing land in partition sales is called the Uniform Partition of Heirs Property Act, not the Partition of Heirs Property Act. “Tenants in common” are not solely defined as those living on a property; they are all those who own a share in the property. The act would not require heirs living on a property to come to an agreement before it can be sold, but would instead provide several other protections.

When talking about the law, it pays to talk to a lawyer.

Freelancers and editorial process

I’ve contributed to publications including The Boston Globe, The Wall Street Journal, and The Harvard Business Review. Not once did these publications check my facts. In some cases, they challenged facts I’d cited or pointed out errors, but it was clear that the responsibility for getting facts right was mine.

This is certainly common practice.

This means that when you read a contributed article or bylined article by a freelancer, the publication is counting on the freelancer to get the facts right. And freelancers don’t abide by the same journalistic standards as employees of the publication.

(I’m not saying that employees of publications make no errors, but they’re generally trained in journalism and make proportionally far fewer errors than op-ed writers and other non-employees contributing to those publications.)

The number and prevalence of contributed articles has swelled enormously. Publications have space to fill; writers want to get paid or have a point of view they’d like to share.

In some cases, like Forbes, the contributing writers have hardly any supervision at all. In my experience, publications like The Boston Globe and The Harvard Business Review have far more demanding editorial standards and require significant editing and rewriting. But editors’ comments typically refer to theme, content, grammar, and bias, not facts. The responsibility for getting the facts straight clearly lies with the writer.

Should publications publish only their own writers’ work? This is unrealistic.

Should they check contributors’ facts? This is unrealistic, too; it’s just too labor-intensive.

Instead, publications must depend on contributors’ reputations. And as a reader, you must, as well. When you read an article by a contributor, do not assume it is up to the same journalistic standards as the rest of the publication.

And as a contributor, get your damn facts straight. Or you might end up as embarrassed as Korsha Wilson is right now.

In your first line…. “an article titled”… what?

Thanks. As usual edits cause other problems. I an article about corrections!

I saw that yesterday and was stunned that that many errors, omissions and misstatements were made. Thank you for highlighting and explaining some of the “why”. I went back to reread the entire article I read last week to be sure I “got it right.” Unfortunately I don’t think others will always do the same.

“And freelancers don’t abide by the same journalistic standards as employees of the publication.” This is not always true. As an occasional freelance writer, I was classically trained as a journalist and accept nothing but 100 percent accuracy in the articles I submit, the marketing pieces I write and the press releases I distribute. The same can’t be said of some of the companies I have submitted my work to for publication.

A blanket statement like this is nothing less than, well…inaccurate.

So is this the same publication that won multiple Pulitzer Prizes and broke the Watergate Scandal? Just shows what can happen to a great brand when it sells out.

How… was this in the food section?!

At least Washington Post publishes corrections. Wall Street Journal guest columnists routinely make stuff up. I used to send letters noting errors to no avail and gave up. An op ed a few years ago about the Tax Policy Center’s track record stated that TPC has a long record of erroneous predictions dating back to the Reagan Administration’s 1981 tax cuts. TPC started in 2002.

Part of the problem is that the Post included a byline but gave no indication of Ms. Wilson’s status. Nothing to say that she isn’t a staffer, that she’s an independent contributor.

It’s a lot to ask a reader — even the most discerning reader — to assess an author’s bona fides when they have only a name to go by. And most readers aren’t that discerning. Not even readers of the Washington Post (gasp).

I understand that a paper can’t fact-check its contributors. But it can easily provide a one-sentence bio — as, in fact, is done on most editorial pages.

That correction is a colossal embarrassment for any news organization, particularly the Washington Post. Running it in the food section was baffling.

Ms. Wilson obviously had a story to tell and a belief to peddle and wasn’t going to let facts get in the way.

By the way, freelancers are a mixed bag. You get everyone from former journalists to those with very little talent – and apparently little ability to conduct factual research.