To Jeffrey D. Sachs: sprinkling tech on politics makes it worse, not better

In an op-ed in today’s Boston Globe, the influential economist Jeffrey D. Sachs laments the lack of trust in modern American politics. He then proposes that we solve it with (among other things) “e-parties” and “e-governance.” But proposals like this ignore the way that trolls and partisans now wreck every online social space.

Sachs’ op-ed, one of a series, is titled “Restoring civic virtue in America. He starts with this:

The direst threat American society faces today is the collapse of civic virtue. By that, I mean the honesty and trust that enables the country to function as a decent, forward-looking, optimistic nation.

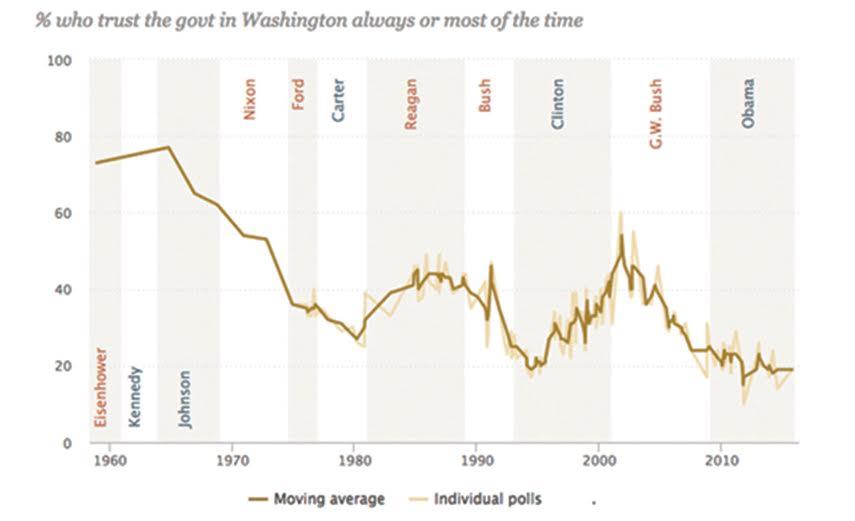

I’m with Sachs on this. The end of trust is a huge threat to our nation, because it undermines the connection among individuals, their elected representatives, and their government. It’s not much of a stretch to see the recent presidential election as a repudiation of government (while the establishment candidate Hillary Clinton won more votes, 46% if the population voted for Donald Trump, a candidate who portrayed government as a swamp to be drained). The Globe’s graphic of data from Pew documents the steady erosion of trust.

How did we get here?

Here’s how Sachs describes the causes of this problem:

American faith in government is in free fall. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, more than 70 percent of Americans believed that government could be trusted “always or most of the time,” compared with just 19 percent who said the same at the end of 2015.

. . .

There are four interrelated reasons for these downtrends: (1) the rise of the secretive and duplicitous US security state, which has left a deep divide between the public and the federal government; (2) the sharp widening of the inequality of wealth and power since the early 1980s; (3) the impunity of the rich regarding the rule of law; and (4) the precipitous decline of political parties as vehicles of political participation and their replacement by the mass media.

All of these reasons are valid. But Sachs has discounted the polarization of news that happens on Facebook. If you’re conservative, your news feed consists of a steady stream of Fox News articles, biased sources like Breitbart, and fake conspiracy theories. If you’re liberal, you get The New Yorker, biased sources like OccupyDemocrats, and a different set of fake conspiracy theories. Your news sources are telling you not to trust the other side, and that Obama and Clinton and Pelosi — or Trump and Price and Ryan — are the devil incarnate. Might this have something to do with the decline in trust that characterized this election season?

E-government and e-parties won’t solve this problem

Sachs delivers a thoughtful set of prescriptions to solve the problem, including reducing the influence of rich people in politics, getting the Supreme Court to reverse its ruling that corporations are people as far as political speech goes, and barring former officials from lobbying. That’s all well and good, if very difficult to accomplish. But what caught my eye was his last and most detailed suggestion that technology is the solution to getting people to participate in government:

[W]e need to regenerate citizen participation through new forms of politics. One key possibility is through e-governance, using the arrival of universal broadband to implement a series of deep governance reforms. These would include: e-voting (online voting); e-drafting of legislation (a kind of Wikipedia for legislative drafting); e-deliberation by citizens through online public debates; and e-parties. Over time, with enough experience and safety valves, we could move to e-votes on key legislation and decisions on war and peace.

An e-party would interact with its members not only at election time but year round. The e-party would treat its members as responsible, engaged, and democratic citizens, through online voting on party platforms and positions, and decisions on party positions on key issues of the day, including the budget, taxes, environmental regulation, and of course war and peace.

E-governance has the potential to undo the single deepest flaw of our current politics: the vast gulf between the public and actual decision-making, which is now in the hands of elected officials who represent powerful vested interests and the superrich more than the voters. Political parties used to help ensure that elected representatives truly represented their constituents, but big money broke that bond. Now e-governance has the potential to enable a 21st-century form of direct democracy, one where we are no longer dependent on distant representatives to do our bidding. Of course for this to work, we need not only the mechanisms of direct democracy but also a citizenry that is well informed, morally engaged, and practiced again in direct political participation.

This is wishful thinking. Frustrated with the traditional forms of citizen participation, Sachs has latched onto technology as the solution to our problems. If only this would work.

How online social technologies destroy trust

Here’s the problem:

Free speech plus technology equals a troll explosion. There’s no way around it.

In online social spaces, trolls can act in tandem to destroy and poison any discussion. In the most recent election, a tiny minority of hateful people on the far right used these methods to benefit Donald Trump. But this isn’t about Trump or the self-described “alt-right” — it’s about the susceptibility of algorithm-based online social spaces to trust-destroying, post-factual partisan stupidity.

I was a big fan of the potential of social media for thoughtful discussion; I cowrote a book about it. But take a close look at what’s happened recently:

- Anti-semites, racists, and sexists have duped Google with a massive collection of hyperlinks. As The Guardian’s Carole Cadwalladr recently described, if you typed “Are jews” Google’s top suggestion for autocompleting the query was “Are jews evil?” (Since The Guardian published its article yesterday, Google has fixed this specific problem, but there are plenty of other examples.) Enough people placing ads, publishing swill, and linking can fool Google into up-ranking reprehensible content.

- A colony of Trump backers on Reddit have gamed the system to drive biased, questionable news articles into the site’s main page, r/all. As Gizmodo’s Bryan Menegus describes, members of a subreddit called r/The_Donald have subverted the site’s laissez-faire ethos and evaded the few rules it has to prevent this sort of rampant mob nastiness.

- Fake news is an industry on Facebook. Buzzfeed’s Craig Silverman and Lawrence Alexander revealed how teens in Macedonia generated over 100 fake news sites, generating the raw material for so much of the inaccurate propaganda that now spreads across the social network.

- Trolls have overrun Twitter. For ten years, Twitter has tried and failed to rein in the proliferation of exploitive trolls opening Twitter accounts. As Buzzfeed’s Charlie Warzel revealed, the site’s dedication to free speech has made it “a honeypot for assholes,” and no one inside the company has the will to fix it.

- Online voting machines are subject to fraud. There’s no evidence that fraud took place in this election — yet. But if it hasn’t already, it will. As Dan Goodin describes in Ars Technica, e-voting machines are insecure and hackable.

These are not isolated cases. If you set up a social space and invite people to participate, trolls and partisans will ruin it.

It’s not easy to tell a troll from a person. You either use an algorithm — which people can game — or depend on the judgment of a set of unbiased volunteers (that’s how Wikipedia does it). But then you’ve got another problem — who picks and vets the volunteers, and how do you prove they’re unbiased? The problem with the volunteers is that they don’t scale, and their judgment is subject to criticism.

Sachs’ prescription for saving democracy is naive. I wish cool words like “e-government,” “e-voting,” “e-deliberation,” and “e-parties” would save our republic. But recent history shows they’re more likely to attract bad actors who will destroy their effectiveness for all of us.

I can see only one way out of this. It is for Silicon Valley to fund a set of of non-profits dedicated exclusively to solving the troll problem, making solutions for identifying trolls and their work available to Google, Facebook, Twitter, and every other social solutions provider. This is going to take years. But it’s a hell of a lot more realistic than just adding “e-” to the front of our democratic processes and hoping that will fix everything.

*APPLAUSE* Love the idea of a new category of nonprofit, tasked with “solving trolls,” and I’ll prepare my resume now for the day when such a NPO ever forms. I agree that the problem is far too pervasive to be solved quickly/easily (or with technology/e-anything), especially in the U.S. where freedom of speech is enshrined in our foundations. But it has to be done by somebody, otherwise our society will just continue to fracture and the damage will be harder and harder to repair.

That graph is revealing. Our trust in government went through the floor during Watergate, as I’d expected. But it had already begun to fall off significantly during the Vietnam era.

And you’re right: it’s going to take a lot more than an “e” prefix to restore that lost trust. Good read.

Josh, enjoyed your post. An additional risk of e-governance of any kind is the potential for foreign governments or other enemies to game, manipulate, corrupt or bring down any web-based organization.

I (and basically every computer programmer who doesn’t work for an voting machine company) have long been of the opinion that when it comes to use voting machines, it’s OK to use machines to help prepare a human-readable ballot, and it’s OK to use them to count human-readable ballot, but not both at the same time. There must always be a human-readable/countable ballot that gets walked across an air-gap.

That way if a vote-preparation machine gets subverted, it can get caught by people checking the ballot it produces before it gets inserted into the vote-counting machine. And if the vote-counting machine gets subverted, the paper ballots can be counted manually. Defense in depth.

Mark-sense ballots are an example of this; currently the preparation machine is a pencil, but it could potentially be a machine that makes entry easier for disabled voters, and which checks that you didn’t miss any races, etc, and then prints out a ballot.

Moving to a voting system that doesn’t require tactical voting (ie: STV variants) is an argument for a different time 🙂