How to write Chapter 1 of the book that will make your reputation

You want to write a book that will make everyone take notice of the insights you’ve gained — insights that no one has thought of before.

But how to start?

I’m going to assume you have a powerful idea and you’ve researched it. (If you haven’t, nail those down before writing.) If you have a bunch of material and you’re ready to start writing, what exactly are you going to write?

It’s a crucial question, because you’re setting the direction for the rest of the book. But based on my experience coaching authors and writing, collaborating on, and editing books, it’s one that authors have trouble with.

Just to be clear, the advice here applies to books intended to make you a respected thought leader. This is not about memoirs or historical tomes or fiction. It’s about books intended to showcase ideas.

Ditch the introduction

The first question is, “what exactly is the start of the book?” Is it Chapter 1, or the introduction?

I’ll solve that problem for you. Don’t write an introduction.

Introductions tend to be introspective. “I had been working in healthcare for twenty years when I realized we need a book on how important nurses are.” Well, frankly, who gives a crap.

The problem with introductions is simple: some people read them and some don’t. That means when they get to the start of Chapter 1, they may or may not have read the introduction. It’s hard enough writing to a diverse audience without puzzling out how to write differently depending on whether they’ve read the introduction or not.

(In earlier times, when readers were more patient, you could indulge yourself and assume they would read your introduction just because you put it there. This still applies if your name is Malcolm Gladwell or Michael Lewis or Daniel Pink. But since that’s not your name, you don’t get to make that assumption. A lot of today’s readers are going to skip your introduction.)

You have once chance to grab the reader by the throat and get her to pay attention. You should concentrate all that effort on putting your best stuff in Chapter 1. The stuff about how you learned what you learned, what you were thinking about, and how the book is organized — as I’ll show, you can get that into Chapter 1, too. Just not at the beginning.

There’s also your energy to consider. You should be concentrating all your formidable writing energy on making Chapter 1 awesome. Why divert some of that to an introduction that not everyone will read?

The same comments apply to prefaces and anything else that appears before Chapter 1. The only exception is if you have a famous person writing a preface, like Dan Rather or Colin Kaepernick or Barack Obama. You put their name on the cover of the book, and that sells books. Their preface probably won’t be very good, but it won’t interfere with the story you’re trying to tell, so at least it won’t create problems for you. You can just write Chapter 1 as if there were no preface.

Start with something compelling

Here are the openers of some of the books I like best (and yes, I wrote or edited a few of these).

She was the scientists’ favorite participant. Lisa Allen, according to her file, was thirty-four years old, had started smoking and drinking when she was sixteen, and had struggled with obesity most of her life. [Charles Duhigg, The Power of Habit]

There is no one way to write — just as there is no one way to parent a child or roast a turkey. But there are terrible ways to do all three.” [Ann Handley, Everybody Writes]

Half past noon on Saturday, May 1, 1915, a luxury ocean liner pulled away from Pier 54 on the Manhattan side of the Hudson River and set off for Liverpool, England. Some of the 1,959 passengers and crew aboard the enormous British ship no doubt felt a bit queasy — though less from the tides than from the times. [Daniel Pink, When]

Rick Clancy seemed worried. Rick is fifty-ish, powerful-looking man with graying hair and, until today, a confident manner that always reflected his control of the situation. In his role as head of communications for Sony Electronics . . . [Charlene Li and me, Groundswell]

Learning to play Go well has always been difficult for humans, but programming computers to play it well has seemed nearly impossible. [Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson, Machine, Platform, Crowd]

Kevin Peters sat alone in his car in the rain, watching the entrance of an Office Depot store. He was wearing a baseball cap and a well-worn pair of jeans. Over the course of the last half-hour he’d watched one customer after another emerge from the store. None of them carried a shopping bag. [Harley Manning and Kerry Bodine, Outside In]

It was October 23, 2008. The stock market was in free fall, having plummeted almost 30 percent over the previous five weeks. [Nate Silver, The Signal and the Noise]

The tide of bullshit is rising. [Me, Writing Without Bullshit]

These are not all the same. Most are stories, like Duhigg’s, the one Charlene’s and I wrote, and Manning and Bodine’s. But others are striking statements, like “The tide of bullshit is rising” and “There is no one way to write.”

You can also start with a personal story if it’s interesting and relevant enough.

Whether you start with a story or a statement, you must start with something that immediately hooks the reader. You should plunge them into the rushing river that is your idea.

That opening has three equally important jobs to do.

First, it must compel the read to read on. If it doesn’t hook the reader, she won’t keep reading. If she’s in a bookstore, she’ll put the book down and walk away.

Second, it must set the tone. It says, in essence, “This author is saying things worth saying in an enjoyable way.” The reader’s assumption is always that the rest of the book will read pretty much like the opening. That is a lie, of course; the opening is your best writing, and the rest of the book isn’t going to be this good. But the promise, at least, must be that your writing is fascinating.

Third, the opener must create the seed of an idea. If it is a story, it needs to have a point. That point should be the point of the book. You don’t want the reader saying, “OK, but why did I just read that?” You don’t set the reader up without a payoff.

Next, make your point

By the end of page 4, we need to know what your book is about. We need to know that media is collapsing and this threatens democracy, or that habits drive our lives in unsuspected ways, or that social media is going to change the way companies relate to consumers forever.

The point of the book belongs right there, on pages three and four. If it’s startling enough, it might be on page one.

Don’t be coy. Readers are too impatient for coy. Explain what you know and why you know it.

The “make your point” section is both enjoyable to read and persuasive. Like the opener, it compels the reader to read on.

It should also be short. If you have sixteen points to make, you don’t have a book. One of those points is central. Make it. And then move on to explaining it in the next section.

Prove your point

Once you’ve made your shocking and counterintuitive point, the reader is naturally thinking, “That’s a pretty amazing statement. What makes you think it’s true?”

This is where you crank out the statistics, the proof points, and the ironclad reasoning. It’s where you reveal what you’ve seen that no one else has seen.

This section should be packed with enough information to be convincing, but short enough to get through quickly. It’s not a research paper. You need to get the reader to put her skepticism aside long enough to keep going. You’ll have plenty of space to prove things in a more compelling way in the rest of the chapters.

This is also where you can get a little conversational about your personal experience. “In 15 years and after treating thousands of patients, I realized something.” That’s part of your proof, and it doesn’t have to languish in a perhaps-read, perhaps-not-read introduction.

Lay out your framework

If your point was simple, you wouldn’t need a book to explain it; an article would do. If you want to use this book to create a reputation for yourself, you need more. You need a six-step process. You need a three-part framework. You need an analysis that applies across five types of industries. Whatever that structure is, here is where you lay it out. This is where you also show your “money graphic” which explains the point in a different way. (And for lord’s sake, please keep that graphic simple.)

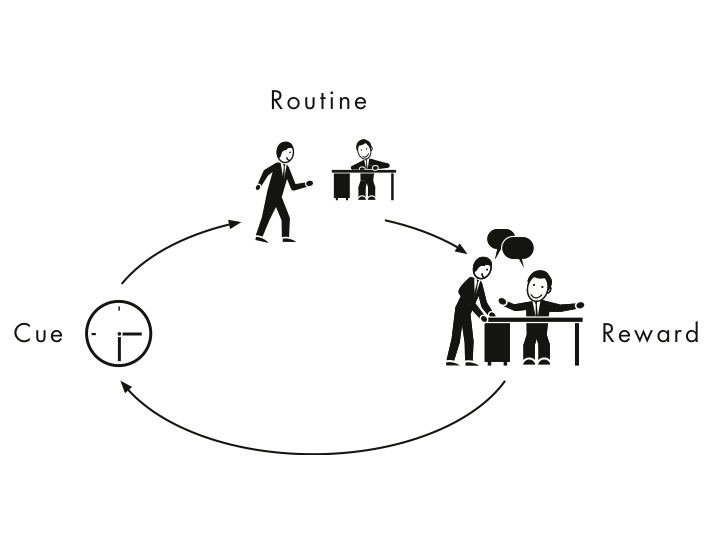

Here’s one of Charles Duhigg’s graphics about habits, for example:

That’s far from the greatest graphic ever shown, but if you read the book, you see how it becomes an iconic part of what Duhigg is describing.

Tell the reader what’s coming

Having sucked us in with a story, made your main point, backed it up, and elaborated on it, you now have room to explain the rest of the book.

In no more than a page, describe what’s coming — for example, the rest of Part 1 describes the way we proved our point, Part 2 explores the stages in detail, and Part 3 explores how this will be different in the future.

This type of signposting is typically done at length, and ineffectively, in introductions. Here you get to focus the reader’s attention on what is coming up and why it is important. More than one page of detail on that is self-indulgent.

Chapter 1 must be the “scare-the-crap-out-of-you” chapter

One more thing.

All Chapter 1s in books of this type are similar. They are intended to scare the crap out of you.

This takes two forms, which I can briefly describe as “fear” and “greed.”

In a “fear” chapter, you describe how something is happening that will threaten the way we work (or think, or vote, or whatever). It’s dangerous and it’s coming soon. The status quo will no longer work. You need to prepare for the new way of doing things.

In a “greed” chapter, you describe how a trend is creating enormous opportunity. You are going to miss out. You could be one of the first to take advantage of the trend. It will make you happier, more productive, richer, or better off in some other way. Stick with the status quo and you’ll end up left behind with the mass of unhappy people. You need to prepare for the new way of doing things.

You can, of course, combine fear and greed, but you should primarily focus on one or the other.

Whether you choose fear or greed, an effective scare-the-crap-out-of-you chapter explains why the status quo is not good enough and why you have to change, and then goes into a little detail to explain what makes the change inevitable and what the elements of that change are. But the level of detail is limited — that’s for the rest of the book. The key is to leave people feeling scared that they will miss out, but hopeful that you can help them.

The way to create this feeling is not with exclamation points and italics. You should make it calmly and clearly. The events and solutions you describe are what are compelling. A cold, clear description of a disaster is far more effective than shouting at the top of your lungs.

The bigger the scare, and the better the solution, the more successful your book will be — if you’ve made the writing tell the story.

There is no more important place to do that than in Chapter 1. Now you know how to do it. Get to work!

What great advice! You completely changed how my co-author and I are beginning our book on women who are fired and how they coped emotionally as well as practically. Start with a fragment of the story of a woman who was fired! Thank you for providing such great content and value in this and other blog posts.