How to run a workshop by videoconference

Workshops are a great way to train people. They can continue even when people are unable to gather in the same room, or leaders are unable to fly to present them. You just have to work a little harder to engage the participants.

I’ve delivered 27 clear writing workshops so far. Three of those were delivered via videoconference, connecting me with remote attendees in their conference rooms and home offices. Those clients included a research and peer-support organization, a large social network, and a tech startup.

Many of the techniques that work well for in-person workshops also work well by video, but others need to be reimagined. The insights I’ll share here would remain relevant regardless of the content of the workshop — most would apply to any kind of training workshop, whether it’s on diversity, efficiency, management, using a new tool, or any other topic.

Start with two fundamental principles:

- Workshop content includes information, experiences, and lessons generated from those experiences. None of that changes depending on the delivery method.

- Effective workshops must engage the attendees and encourage them to think. That’s much harder when the attendees are not in the room with you.

With those principles in mind, here are some tips:

Make sure your delivery technology is rock-solid

If there are technical difficulties in an in-person workshop, you can call the AV staff and charm the attendees while the techies fix the problem. That’s not an option from your home office. I’d never want to let down a group of 20 or more people who have all gathered for several hours to hear me. To enable dependable delivery, you need to make sure you have all of the following rock-solid:

- Connectivity. I have a wired ethernet connection that delivers 900 Mbps. Wired is more dependable than wireless, and consistent bandwidth is a must for workshop delivery. In an emergency, I could use a tether to the internet connection from my phone, but that would be a poor alternative (and one I’ve never needed).

- Computer. I have a new MacBook Pro and a backup machine. Both are up-to-date with the same files and applications through cloud backup.

- Videoconferencing system. I use Zoom videoconferencing, and I love it. In hundreds of meetings over hundreds of hours it has only glitched once, for about 10 seconds. It is both dependable for the presenter and flexible and easy for the attendees, which makes it ideal for this scenario. I pay $150 per year for a plan that allows me to present to up to 100 people at once, which is quite sufficient for an online workshop.

- Electricity. I don’t have electrical backup. In case of an outage my router would shut down but my PC would function on batteries. I’d have to fall back on the phone for internet. If you live in an area with more frequent electrical outages, you might consider a UPS or generator, but that’s overkill for my needs.

You need a dependable partner at the client’s company

My workshops generally take three-and-a-half to four hours, and include a review of writing materials from the client.

There’s typically a manager or HR person who has set up the training. I work with them to ensure that everyone is aware of the timing and to get materials to them in time for the workshop.

My partner on the client end helps with logistics and culture as well. In the case of a remote workshop, they can tell me how familiar people are with connections on software like Zoom, and whether it’s better if I email the participants with instructions on how to prepare, or if they should do it.

In all three of my workshops delivered by video, the organizations were distributed, with people working from home or remote offices. They were all quite familiar with working in remote conferences. (All three were familiar with Zoom, so I didn’t need to worry about that.) This made things much easier for me, since I only had to explain how the workshop worked, not how to connect by videoconference.

If you are working with a company that typically doesn’t connect remotely, it’s best if your partner on the client end helps staff to get used to connecting in this way. I wouldn’t want my workshop to be the first time people had used a videoconference. Conversely, if the organization typically uses a different video system, like Google Hangouts or WebEx, I’d want to test out a few things to make sure I was familiar with the features of the tool before presenting in it.

Your content may be workable as designed — unless you have small group breakouts

Workshops typically include the following types of interactions:

- Presenter speaks, attendees listen.

- Presenter asks questions, attendees volunteer and answer.

- Discussion among attendees and presenter.

- Attendees work on an exercise individually, in parallel, and then everyone discusses the results.

- Attendees break into small groups to work on a problem, then report back.

My workshops include only the first four types of interactions. The content is basically the same as when I present it in person — same slides, same talk track, same jokes, same questions for the audience, same exercises. The only difference is in how I present the material, as described in the next section.

I’ve been a participant in workshops where small groups work a problem, the fifth type of interaction. This is more problematic in remote settings. In theory, the attendees could start their own small sub-conferences of six or eight people, then come back to the full conference after the time period for their work has elapsed. In practice, I think there is a chance that such types of interactions would create a chaotic environment, unless each subgroup has a leader who can manage the group, solve technical issues, and keep everyone in the group on track. If you’ve done such breakouts remotely, I’d love to hear how you managed it.

You need to put extra effort into engaging the audience

This is the biggest challenge. When delivering an in-person workshop, I roam the room. I look out at the audience frequently, ask questions, and interact with individuals. I look for people who may have mentally “checked out” and interact with them to bring them back into the flow.

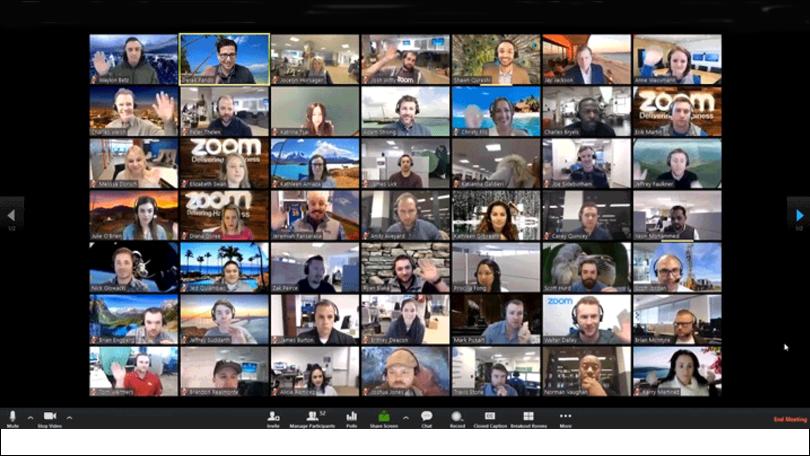

It’s much harder to do this by video. You have a bunch of small thumbnails of people’s faces to look at, instead of a room of people in chairs. To make up for that challenge, I more frequently ask people if they have questions or comments, and carefully observe the heads nodding up and down — or not. I encourage more interruptions and discussion.

The key thing to recognize is that it’s very hard for people to concentrate on a screen for hours at a time, no matter what is happening on it (and I’m not as exciting as an action movie ). You need to have some empathy for the people in the training, and acknowledge this.

As a result, anything that breaks up the flow of presenter delivering and attendees passively listening is a good thing. I encourage questions, try to answer them thoughtfully, and engage the other attendees (“Does this align with your experience? Do you think my suggestion would work?).

The exercises are a particularly important part of this engagement. Here is one place where my use of writing samples from the company pays off, especially when some of those sample were written by the people participating in the workshop. I ask people to identify problems and describe how they would solve them. I engage other people to contribute their own solutions and explain why they chose them. There is no “right” answer in most of my exercises, which makes a discussion of alternative answers into a valuable and engaging part of the workshop.

I also call on people to contribute individually (“Who here is working on a writing project right now? All right, Sally, who is your audience? . . . “). This breaks up the constant stream of me talking and others listening.

I take frequent breaks, at least one per hour, of ten or fifteen minutes, to give people a chance to get away from the session and take care of other needs. One thing to be cognizant of us that people in the same session may be in different time zones. A mid-afternoon break for one attendee may be a lunch break for another one, and it pays to give them time to get something to eat.

Here is a good place to note that these sessions are much harder on the presenter then a typical in-person workshop. While you may not be striding up and down the aisles, you are intensely concentrating on the faces and needs of the attendees. Doing that for three or four hours is hard. You need breaks as much as the attendees do.

Use the features of the videoconferencing system to enrich the experience

While you don’t have the full interactive experience of the in-person workshop, systems like Zoom offer other elements that can be quite useful.

First, you can share anything on your screen. This is essential when sharing slides, but also useful for sharing examples like web sites or documents. You can use tools like Google Docs to edit in real time based on interactions with your attendees, creating a sort-of whiteboard for brainstorm sessions. (Be careful with screen sharing, though — it’s easy to inadvertently share confidential information that may be up on your computer screen.)

There is also a chat channel in most videoconferencing systems. At one company for which I did a video workshop, attendees were accustomed to using chat as a sort of back-channel for conversation during the conferences. I found it useful as a way to keep an eye on the state of the audience and catch problems. At another organization, the chat channel was a useful way for them to provide answers for my questions and exercises.

With the real estate needed for sharing your own screen, viewing video from others, and monitoring the chat channel, you’ll be better off with multiple monitors.

I found one other technique useful. I conduct a Q&A session at the end of each workshop. But it’s useful to ask people who are particularly interested to stick around, and allow the others to leave. This creates a small group interaction of five or six people, much like the experience of the small gathering that happens with the speaker after an in-person workshop. The more intimate back-and-forth from that additional little scrum can be valuable for those who have more detailed or more specific questions.

Video workshops are the future

The recent virus-prompted move towards more working from home could challenge the world of in-person training. Based on my experience, with proper preparation, a video workshop can work extremely well, duplicating or even exceeding the experience of a workshop in a room full of people. The key is for both the leader and the organization to work a little harder to improve the interactive experience for every person who attends.

Very timely and useful. Thanks!

A company where I work uses Zoom and Adobe Connect for virtual meetings, but tends toward Adobe Connect for training/learning programs. It’s much more expensive, I believe, but managing virtual breakout groups is relatively seamless. That said, we nearly always have a co-facilitator or Adobe Connect “producer” available (and sometimes present) in the breakout rooms to help manage questions. As with in-person small group work, how we set up the activity is crucial: clear tasks (what to discuss and do as a small group), timing (how long to discuss versus do), and outputs (who will report, what points to cover when back with the large group).

Thanks, Jaime, for answering the question of how to manage the small groups. Very helpful.

Breakout rooms (a feature in Zoom) are a fantastic way to still do small group work. You can put people into different size rooms (2 people, 3 people, etc), give them instructions, and then bring them all back after a period of time and debrief as you normally would.