Where Esquire went wrong: promoting a Jeff Jarvis impersonator

I’m all for satire, especially on social media. But when traditional media get involved, they must set some boundaries. That’s what didn’t happen when Esquire published an article by a Jeff Jarvis impersonator.

I’m all for satire, especially on social media. But when traditional media get involved, they must set some boundaries. That’s what didn’t happen when Esquire published an article by a Jeff Jarvis impersonator.

First, here are the facts about what happened.

- Jeff Jarvis is a media critic, author, blogger, and professor at the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism.

- “@ProfJeffJarvis” is a satire Twitter account, apparently run by a guy named Rurik Bradbury.

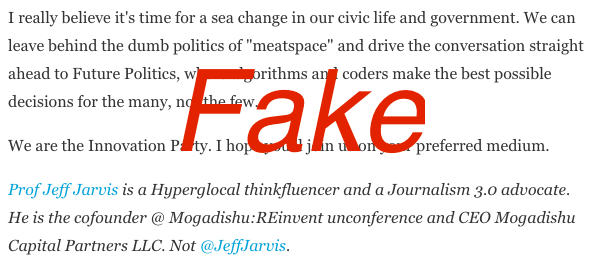

- Esquire published a satirical article, bylined by “Prof. Jeff Jarvis,” that lampooned Jim VandeHei’s op-ed in the Wall Street Journal calling for a third political party. At the very bottom of the article (shown above) is the description of the author, which is pretty murky.

- Jeff Jarvis protested and used contacts he had at Esquire’s parent company Hearst to get the article taken down. He wrote about his experience on Medium. (If you’re curious, it’s still archived here.)

In this saga, my sympathies lie with Jeff Jarvis. But satirists have a right to publish satire, and publishers have a right to publish it. Where did things go wrong?

I’m fine with clearly labelled fake social media accounts (although @ProfJeffJarvis isn’t labelled particularly clearly). And I’m fine with satire in mainstream publications, although it needs to be tagged as such. I’m peeved at fake sites like nbc.com.co which skirt the edge of pretending to be actual media sites, but they have a right to exist.

But when you read an article on a traditional media site like Esquire, satire or not, it needs an actual byline. Made up individuals don’t get to write there. They’ve got the whole rest of the Web to play with.

Once a news outlet loses its credibility, it’s got nothing left. Given the current state of media, that’s a dangerous choice.

Correction: This article originally stated that Jeff Jarvis was at the Columbia School of Journalism. His professorship is at the City University of New York, not Columbia.

For the record, the real Jeff Jarvis teaches at the CUNY (City University of New York) Graduate School of Journalism not the Graduate School of Journalism at Columbia University.

Spotted that as soon as I published, it’s fixed in the article and there’s a correction. Sorry about the error.

“But when you read an article on a traditional media site like Esquire, satire or not, it needs an actual byline. Made up individuals don’t get to write there. They’ve got the whole rest of the Web to play with.”

Are you saying no one can use a pseudonym for a byline on a ‘traditional’ media site?

I don’t think pseudonyms on traditional sites are a good idea. In some cases where people need to hide their identity for safety, I understand.

Spencer F. Katt and Robert X. Cringely existed, I know, and Perez Hilton exists. But at least in those cases, the pseudonym is a consistent persona not intended to confuse. Even so, I think characters like them are a bad idea on media sites in the current confusing media landscape.

But the worst idea is a writer who is pretending to steal the identify of another person — I don’t see any justification for that in a byline on a media site.

“But the worst idea is a writer who is pretending to steal the identify of another person — I don’t see any justification for that in a byline on a media site.”

Do you think that’s what’s going on here? I think he’s clearly used “Prof. Jeff Jarvis” to satirize Jeff Jarvis-style optimism about tech.

@ProfJeffJarvis is not your average satire account. Except for the “Not @JeffJarvis” in the Twitter description, it looks like a real account (especially if you don’t look close). That’s a little shady, but on social media, it’s OK.

However, when it appears as a byline on a traditional media site, the “jokey” persona isn’t very visible. It’s a lot easier to get confused. That’s why the real Jeff Jarvis got upset. And that’s why I think, once the fake byline appears on a real site, you have a problem.