Applying “Games People Play” to writers and editors

In the 1964 bestseller “Games People Play,” Eric Berne showed how transactional analysis (TA) explains emotional conflict. In TA, people interact in one of three roles: parent, adult, or child; when roles get confused, people get upset. These same kinds of conflicts occur, for similar reasons, when writers and editors aren’t clear about the roles they’re playing.

In the 1964 bestseller “Games People Play,” Eric Berne showed how transactional analysis (TA) explains emotional conflict. In TA, people interact in one of three roles: parent, adult, or child; when roles get confused, people get upset. These same kinds of conflicts occur, for similar reasons, when writers and editors aren’t clear about the roles they’re playing.

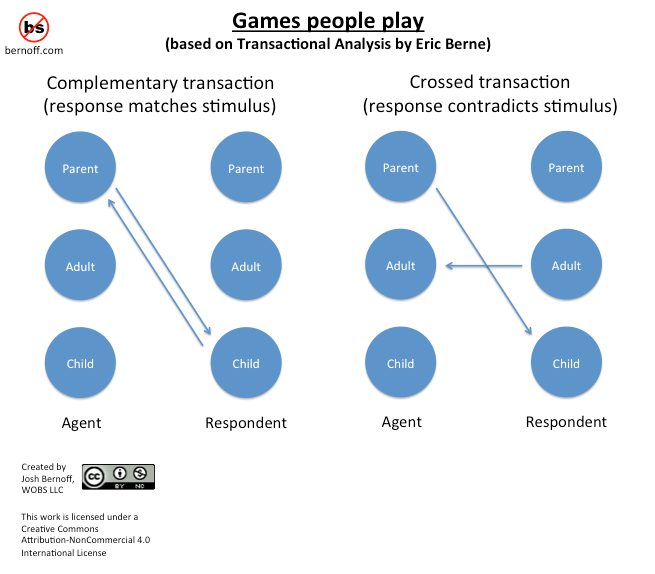

Here’s the briefest possible explanation of TA. The three roles aren’t literal, but symbolic. Parent represents interacting in a teaching mode, adult in a rational mode, and child in an emotional, “feeling” mode. In a complementary interaction, as Berne shows in his diagrams, both participants have a common understanding of how they are interacting. When I interact as a child (“Take care of me”) and expect you to respond as a parent, and you actually respond as I expect, nobody is frustrated. But in a “crossed transaction,” the respondent disrupts the transaction by responding out of character: I behave as a child toward a parent, but you respond adult-to-adult. This upsets people.

This approach reveals why the emotional side of editing relationships often blow up in ways that writers and editors don’t expect. It’s because editors and writers have different ideas about what their roles are supposed to be. The analogous roles in editing are Teacher/Peer/Student rather than Parent/Adult/Child, but the dynamic is similar. Let’s look a three examples.

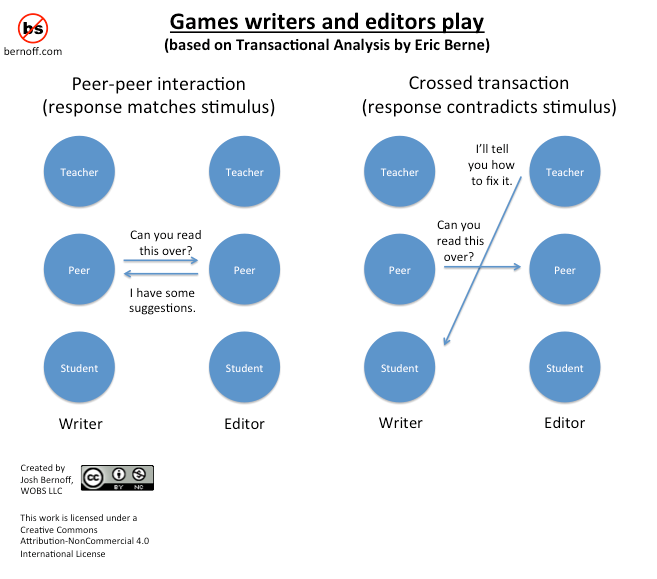

The most powerful editing paradigm: adult-to-adult

I’m an experienced writer. I don’t expect editors to take care of me, I expect them to test my ideas. They make suggestions, then I then take responsibility for solving my own writing problems. When I edit others, I often use this same adult-adult (or peer-peer) paradigm. Here’s a TA-style dialogue of how this looks when it’s working:

Writer (as Adult/Peer): Read this and tell me what you think.

Editor (responding as Adult/Peer): Your structure has redundant elements. I also think the name of your main concept is confusing. I have suggestions about a new structure and a new concept name.

Writer(responding as Adult/Peer): Good points. I have a new idea for the structure that is different from what you suggested, but addresses your problems. And let’s brainstorm new names and see if we can come up with something.

Notice that the writer never gives up responsibility for solving the problem, but the editor is an essential partner. This rational adult-adult interaction leaves everyone feeling helpful and collaborative. When both writer and editor are experienced, it generates great results.

Here’s how it looks when it doesn’t work — for example, when the editor responds as in the parent/teacher role, instead of in the adult role:

Writer (as Adult/Peer): Read this and tell me what you think.

Editor (responding as Parent/Teacher): Your structure has problems. I’ll show you how to fix it. And here’s how you should rename the main concept.

Writer (as Adult/Peer, conflicted): Why are you trying to take over my writing? I just asked for your ideas.

Again, the problem is not what the editor said on even how he said it. It is that he responded in a different role from what the writer expected.

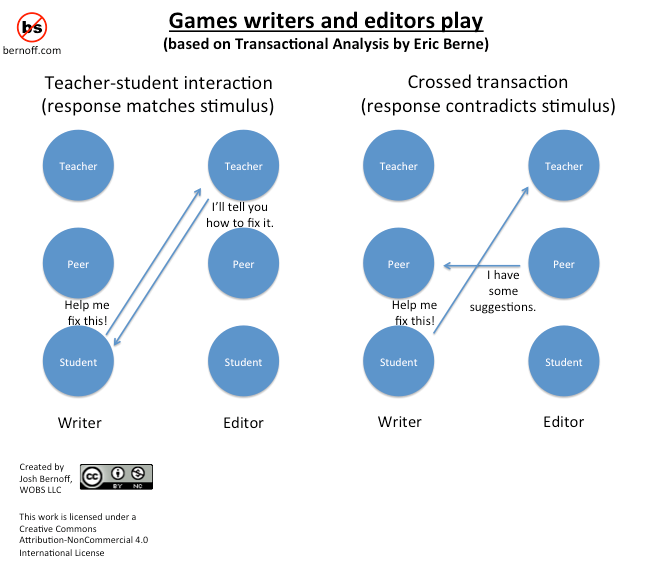

Also powerful: writer as child, editor as parent

When the writer is insecure or inexperienced and the editor is knowledgeable, you can end up with a productive TA parent-child interaction (at work, we’d call this teacher-student). It looks like this:

Writer (as Child/Student): This piece isn’t working. Help!

Editor (responding as Parent/Teacher): Actually, there is a lot of good stuff here. I can see a structural problem and I know how to solve it. And I have a better name for the main concept.

Writer (responding as Child/Student): Wow, thanks. I’ll do what you asked. I feel much better now.

In this interaction, the editor reassures and the writer takes the advice. Writers in such a relationship can learn a lot, but only if everyone understands their roles. Again, look at how this fails in a crossed transaction:

Writer (as Child/Student): This piece isn’t working. Help!

Editor (responding as Adult/Peer): Your structure has redundant elements. I also think the name of your main concept is confusing.

Writer (as Child/Student, conflicted): Tell me what to do. I can’t fix this myself!

Less effective: writer as parent, editor as child

You might wonder if it’s possible for the writer and editor to reverse roles. For example, a senior manager acting as editor may have an emotional (child-type) reaction to a piece of writing. This type of editing works only if the writer is mature and intuitive — so she can figure out what the editor’s problem actually is.

Writer (as Parent/Teacher): Please review this, I hope you’re ok with it.

Editor (responding as Child/Student): This sucks. I hate it. It’s not in line with our brand focus. Fix it.

Writer (as Parent/Teacher): I can see you have a problem with what I wrote. Don’t worry, I understand the problem, and I can make it work better for you. You’ll be happy with the next draft.

—

The point of Games People Play was to make us aware of the scripts we all play out, so we can escape them. My point is the same. If you recognize these crossed writer-editor interactions in your work, try to get on the same page about your roles. You’ll spend more time making writing better and less time gnashing your teeth and resenting each other.

Book photo: Book Worship