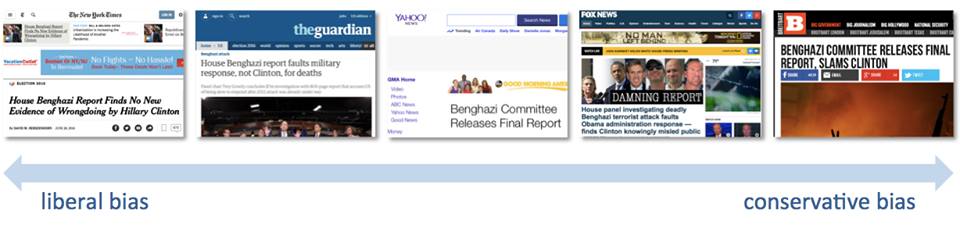

All narratives are biased, as the Benghazi report coverage reveals

Four Americans died in Benghazi on September 11, 2012. Yesterday’s “final” 800-page report about it from the U.S. House Select Committee is biased. So are the response from House Democrats, the coverage from Fox News, the coverage from CNN, and every other article. Why? Because all stories are inherently biased. It’s the nature of the form.

Here’s a fair warning from me to you: if you’re reading this because you want me to decry the bias of news channels and online news sources, you’ll be disappointed. This is the world we live in and everyone knows it. Railing against Fox News or MSNBC does nothing but excite the people who agree with you and anger the ones who don’t. I’m interested in light, not heat, so I’m seeking a deeper truth.

You don’t need to distort facts to create bias

What happened in Libya and around the world on the day of the attack? A man had breakfast. People rioted. An antiterrorist team in Spain failed to leave the runway for three hours. Millions of other events happened. Which ones are significant? Depends on the story you tell.

Committee report from House Republicans (Representative Mike Pompeo):

We expect our government to make every effort to save the lives of Americans who serve in harm’s way. That did not happen in Benghazi. Politics were put ahead of the lives of Americans, and while the administration had made excuses and blamed the challenges posed by time and distance, the truth is that they did not try.”

The State Department’s security measures in Benghazi were woefully inadequate as a result of decisions made by officials in the Bureau of Diplomatic Security, but Secretary Clinton never personally denied any requests for additional security in Benghazi.

House Benghazi Report Finds No New Evidence of Wrongdoing by Hillary Clinton

Ending one of the longest, costliest and most bitterly partisan congressional investigations in history, the House Select Committee on Benghazi issued its final report on Tuesday, finding no new evidence of culpability or wrongdoing by Hillary Clinton in the 2012 attacks in Libya that left four Americans dead.

GOP-Written House Benghazi Report Faults Obama Administration

The House Select Committee on Benghazi faulted multiple agencies for lacking an overall Libya strategy, and it characterized the U.S. government as slow and disorganized in responding to the attacks on two diplomatic and intelligence facilities once they were under way.

House Benghazi report slams administration response to attacks

A damning report authored by the Republican-led House committee probing the Benghazi terror attacks faulted the Obama administration for a range of missteps before, during and after the fatal 2012 attacks – saying top administration officials huddled to craft their public response while military assets waited hours to deploy to Libya.

House Republicans Spent Millions Of Dollars On Benghazi Committee To Exonerate Clinton

After spending more than two years and $7 million, the House Select Committee on Benghazi released a report Tuesday that found — like eight investigations before it — no evidence of wrongdoing by then-Secretary of State Hillary Clinton or other members of the Obama administration.

Online filtering exaggerates bias

Online news tools have trapped in a vicious cycle of bias. Facebook highlights news that matches your own perspectives. This fuels biased reporting, because that’s what’s going to show up in your feed. An article yesterday in Wired nailed it.

Benghazi Report Shows the Internet Is Killing Objectivity

If you were to read the way the left wing and right wing media were covering the newly released report on the attacks in Benghazi today, you could be forgiven for thinking they were referring to two entirely different documents. . . .

It is the beauty and the tragedy of the Internet age. As it becomes easier for anyone to build their own audience, it becomes harder for those audience members to separate fact from fiction from the gray area in between. As media consumers, we now have the freedom to self-select the truth that most closely resembles our existing beliefs . . .

Narrative itself is the root of the problem

If you put serious effort into writing anything intended to be factual, you must do the following:

- Do research to find and verify facts, quotes, and statistics.

- Determine what story the facts are telling.

- Select the facts, quotes, and statistics that fit the story.

- Arrange these elements into a compelling story.

- Discard the rest.

We do this because narrative is central to how we communicate. Narratives have a beginning, a middle, and an end. They connect one event to another. They have a conclusion. Unlike raw collections of facts, they stick with people. This is why everything effective that we write is in the form of a story.

But all stories leave things out. Discarding elements and keeping others is central to storytelling.

All storytelling distorts. It’s inevitable.

You ought to know enough to mistrust biased sources like Breitbart, which decide on the story first and choose the facts to fit. But all writers distort, regardless of their intentions, because they leave things out based on their judgment.

As a reader, you must always seek multiple storytellers. News sources save you time by collecting facts and presenting them in a digestible way. But if you don’t want distortion, you should seek a variety of sources, including those with perspectives you disagree with.

How to compensate for narrative bias

What should you do about this as a writer?

You can’t write without leaving things out. And you must write in the form of a narrative, or no one will be able to comprehend or assimilate what you are writing. Writing without story would be like writing without paragraphs or punctuation — completely ineffective.

The traditional way to create “balance” is to quote people who disagree with a conclusion. This is perfunctory and ineffective. The balance it creates is false, especially when the people you quote are wrong on the facts.

Instead, ask yourself, what stories are the facts telling me? You may see multiple, contradictory narratives.

Don’t just pick one. Try to find the higher truth that subsumes them all. And try to reveal that higher truth.

Follow up. Tell the alternate stories as well in future pieces.

Your job as an unbiased writer is not to skew the reader’s perspective to match your own. It is to tell the stories — plural — that reveal what is actually going on.

So don’t stop with one story. Because the truth is always more complicated than that.

Thanks to Ben Kunz and Sam Mallikarjunan for suggesting this analysis.

Note: I will delete comments promoting one narrative of Benghazi over others. This is about how stories distort truth — not about which truth you believe in. You’re not going to convince anybody, so don’t even try.

Excellent analysis with useful, sound advice.

Josh,

I dig your theory that bias creeps into *communications* because narrative (selection) by necessity requires leaving some elements out (deselection). However, I suggest bias is a deeper part of human nature. We filter and distort almost all the sensory inputs that come at us each day, and how we respond, because we must to survive.

A quick, morbid example: Imagine driving down the road and seeing a dead squirrel on the road. You drive by, unfazed. Next turn, you encounter a dead human child in the street. Horror! You are frightened, pull over, call the police. In reality, one sentient life lost is equal to another; but because we ourselves are humans — and perhaps evolutionarily found aversion to human death good for our species’ survival — we find a child’s death more shocking than a squirrel. The data from each scenario is equivalent, but our views and reactions are different.

This filtering of inputs is vital to survival because our little brains are ill-equipped to process all the data coming our way. Back in 2009, Nick Bilton calculated the average American consumes 34 gigabytes of data a day solely from media such as TV and the web, not counting the chirping of birds, the sight of rainbows or the reminders of a spouse to take out the trash. Our atavistic survival tactic of screening out or accepting data based on preconceptions — when a neighbor yells “Tiger,” accept as fact and run — has been tested by this modern new wave of visual and audio artificial information.

Thus: I’m a conservative who values local government so global warming can’t exist because that would require multinational cooperation and that doesn’t fit my filter that big governments don’t work well. Block: scientific fact.

Thus: I’m a liberal who values nature so GMOs created by big business can’t be healthy because big business is bad and that idea doesn’t fit my core belief that nature is ideal. Block: scientific fact.

We discard most of every touch and sight and sound because we must; distorted screens have helped us manage the world in our past. This warps our ideas, which bend in curves that end in our preconceived beliefs.

We need filters to survive, and all facts that don’t fit the slots are rejected because they are painful reminders that we can’t take in the world at large.

Do trees feel pain when we chop them down? Do ants cry out when we crush them building houses? Are the ocean’s endangered dolphins smarter than us, with more neocortex neurons than humans and the need to process echolocation sounds in water that travel 4.5 times faster than the sound we hear in air? No one cares, because we’re humans, and we care only about us.

It’s too late to fight information bias. It’s who we are. So far, it’s helped humans trump the world. But if a smarter AI comes along with a similar defense mechanism and growth motivations, we may say … hold on a sec, let’s talk about a more equitable view of how the world really fits together.

In the criteria you outlined in writing a factual narrative, do you at any point address the narratives that are factually wrong? Is there an obligation to defuse the motivated reasoning of those readers who insist on clinging to deeply held and factually incorrect beliefs? Or do you ignore that and stick with what you yourself can substantiate?

People who don’t care about the truth are impossible to move. Writers who don’t care about the truth are not in my target market — my advice to them is not to buy my book and not to cross my path.

Looking for a higher truth is absolutely the right advice. As a practice, whenever I am offered two options I immediately ask myself:

1) What biases do these options reflect?

2) What other ways are there to look at this?

The exception is when I’m offered free wine at an industry event. If the bartender says “red or white” I’m not questioning it. I’m a writer and sometime philosopher, not an idiot.